The Grappa through the centuries

When did the production of Grappa begin?

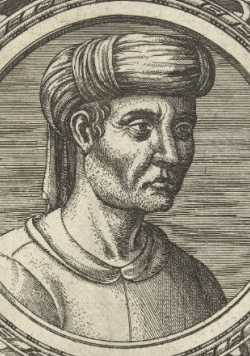

It's not easy to answer such a question. The production of wine distillate, for example, became known when the Paduan physician Michele Savonarola (1384 – 1462) published the first treatise on this subject: "De Conficienda Aqua Vitae". Probably, the distillation of grape pomace began already in the 14th or 15th century, or perhaps even earlier.

Legends and hypotheses: Enrico di ser Everardo from Cividale del Friuli

Many publications dedicated to the history of this distillate refer to a document regarding a certain Enrico di ser Everardo from Cividale del Friuli. It seems that in his will, dated 1451, he left as an inheritance "unum ferrum ad faccenda acquavitem" (a still for distilling aquavitae) and in this context, the term "grespìa" is also mentioned. In reality, there is no evidence to support this anecdote, and the will, never made public, is not available in any archive consulted so far.

Legends and hypotheses: Enrico di ser Everardo from Cividale del Friuli

Many publications dedicated to the history of this distillate refer to a document regarding a certain Enrico di ser Everardo from Cividale del Friuli. It seems that in his will, dated 1451, he left as an inheritance "unum ferrum ad faccenda acquavitem" (a still for distilling aquavitae) and in this context, the term "grespìa" is also mentioned. In reality, there is no evidence to support this anecdote, and the will, never made public, is not available in any archive consulted so far.

Grappa: a popular beverage

Grappa was not a spirit reserved for the wealthier classes, who reserved wine or perhaps the distillate obtained from it for themselves, leaving to the population what remained: namely, the skins, seeds, and stems of fermented grapes. Certainly, Grappa of that time was very different from the distillate we know today. It must have been much drier, saturated with sometimes unpleasant and pungent substances: Grappa passed through the ages with these characteristics of a simple, strong, and burning beverage.

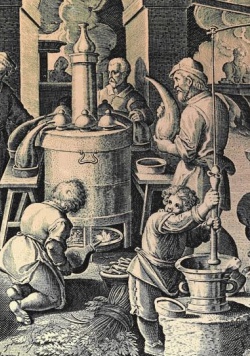

The evolution of production

The Grappa of the past was produced with pot stills or direct fire stills, using a discontinuous cycle artisanal method. Continuous distillation plants were not yet in use, having arrived in Italy only in the mid-twentieth century. Grappas from the distillation of a single grape variety were not yet widespread, although Grappas from Moscato, Prosecco, or Malvasia were already being produced in the early twentieth century, true examples of single grape variety Grappas before the term was coined. The classic Grappa Bianca, the result of distillation of pomace from mixed grape varieties, mainly existed.

The evolution of production

The Grappa of the past was produced with pot stills or direct fire stills, using a discontinuous cycle artisanal method. Continuous distillation plants were not yet in use, having arrived in Italy only in the mid-twentieth century. Grappas from the distillation of a single grape variety were not yet widespread, although Grappas from Moscato, Prosecco, or Malvasia were already being produced in the early twentieth century, true examples of single grape variety Grappas before the term was coined. The classic Grappa Bianca, the result of distillation of pomace from mixed grape varieties, mainly existed.